Mark and I write and speak a lot about Overt Teaching. If you’d like to know more about what that is, you can read our blog post here or check out our handy dandy book, available on all good book websites and probably in the dark corner of a bookshop where they keep the rest of the EFL methodology books.

The core of Overt Teaching is that we believe we should be involving our learners in the discussion of learning throughout our lessons. We should be discussing the objectives of our lesson and helping learners to relate it to their lives and goals; we should discuss why we do what we do with our students, what our aims for a task are; we should give students the tools they need to reflect on their own success and give their peers feedback. And why? Because a more aware and invested student will be more engaged and make more progress.

In general when we talk about this at conferences or just one to one, our points and ideas are met positively. We’ve met very few teachers who really believe that it is a bad course of action or who do not want learners engaged with the learning process. However, we do often encounter some push back and it tends to be in the form of:

This is great but my students couldn’t do this.

There tend to be a number of reasons why teachers believe that their students would not be able to discuss learning but below are some of the most common, and a summary of some of the discussions we’ve had.

This is fine with higher levels but my students are too low. They don’t have the language you need to reflect.

Of all the levels, learning is most tangible at the lower levels. It can sometimes be as simple as “at the beginning of the lesson, you couldn’t talk about the past, now you can”. Very often reflection is viewed as a complex abstract topic that must be delved into in great detail. However, at beginner, elementary or pre-int, reflection at the end of a lesson can be a simple discussion:

- What vocabulary did you learn today?

- What grammar did you learn today?

- How will you use it outside class?

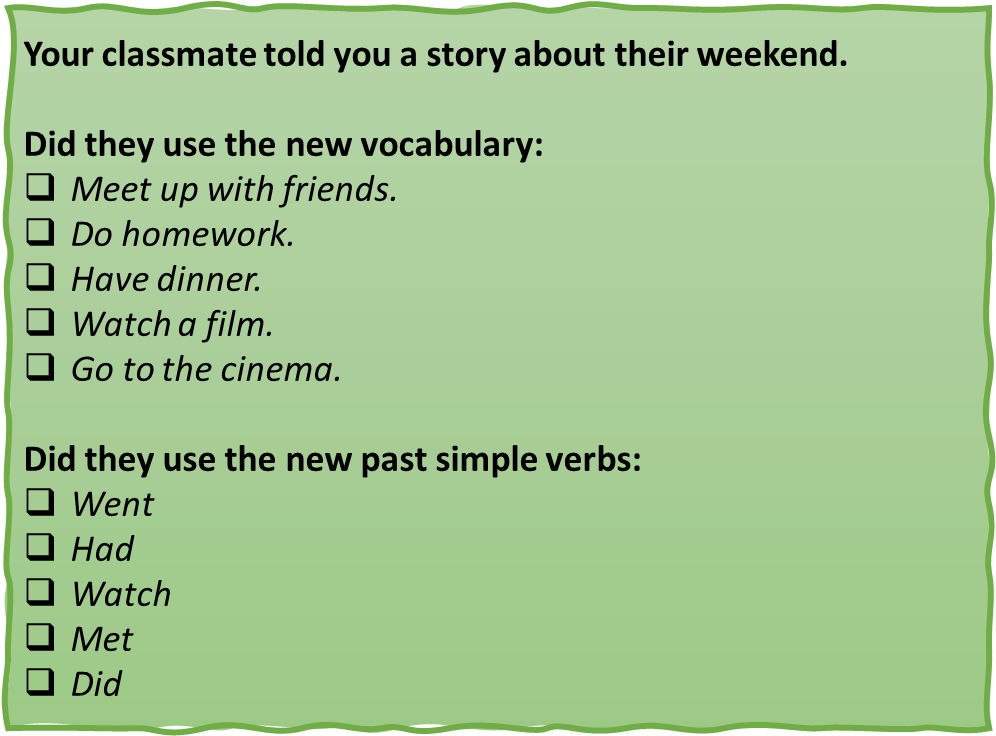

Success for a task can be laid out as using a specific piece of grammar or a number of items of lexis. Students can easily give peer feedback with short tick-boxes. The below can be easily used so students can choose their own lexis and their own level of success. It can be used as a peer-assessment or adapted for self-assessment.

This is fine with lower levels but my students are advanced and it is harder for them to see progress and reflect.

100% agree with the core of this statement. At higher levels it is more difficult for students to see their progress as it’s much less tangible. This, however, makes it even more crucial that learners are given the opportunity to reflect on and discuss what they’ve learnt. Without these discussions, students may come to the conclusion that they are not progressing because it is less tangible and visual.

At higher levels, students can converse easily on a range of topics. They can draw on their known, safe language and complete communicate tasks with relative ease. It is important therefore that we give them the opportunity before the task to make decisions about new language and skills they want to attempt, encouraging them to move outside their comfort zones. And then to reflect on how successful they were and what they want to try next time.

This is fine with adults but my students are too young to reflect and discuss their learning.

Most of my experience has been with older students, and while I have taught younger students, it is a number of years ago now. However, recently I got the chance to sit in on my 5-year-old son’s lesson. He was writing some words about a picture they had drawn. They were learning to write words to describe body parts. The teacher modelled it and then checked success criteria:

- Where do we write? Chorus: under the picture.

- How many words do we write on each line? Chorus: one.

- Which words are we writing? Chorus: body word.

Students went off and wrote their words. Afterwards the teacher asked them to give their partners feedback using thumbs up or down while she moved around. She called out the success criteria again and students gave their partners thumb-based peer feedback.

Like anything, we grade the task. It’s all possible but needs to be scaffolded for the age or level. Here’s a nice idea for teaching writing using images of cupcakes the visualise layers of success.

This is fine but my students are from an educational background where they expect the teacher to give input the whole time. They’re not able to reflect.

There are so many things that we take for granted in an English language lesson that are not standard in every educational background. Depending on your age or culture, working with a partner may not be something you expect in class, but we do it because we know the value. For many students, being taught lexically might jar with their expectations but many teachers will persevere, confident that this is the best way for their students to learn.

Like anything, given the support and scaffolding, students will learn what is expected of them in class. Patience and understanding will often be necessary but if you feel that the discussion of learning is worthwhile and beneficial for them, then it’s worth spending the time helping your learners to develop those skills.

This is fine by my students want to focus on grammar and vocabulary input. There is not time for reflection and discussing learning.

As above really. If you value it, then it’s worth spending the time on it. The expectation of many students is that their lessons should be full of input so they can fill their notebook with notes which they may never look at again. What’s more important than every student knowing how much they’ve progressed in a lesson and knowing what they need to work on. Without discussing learning, this won’t happen. We’ve got to value these discussions and make the space in the lesson.

This is fine but I tried to do reflection tasks and my students couldn’t do it.

Giving peer feedback, reflecting on success or discussing your progress are not easy skills. However, they are skills that will help our learners in language learning but also in their lives beyond the classroom. They are valuable skills. The first time you try it with your students, they may struggle or balk as reflecting on input isn’t as easy as receiving and recording input for many. My advice would be:

- Scaffold it carefully.

- Do it little and often.

- Don’t be put off if it’s tricky the first time. Persevere…it’s worth it.

This is fine but there are 50 students in my class so I can’t do this with them all.

The bigger your group, the more crucial it is that your learners are developing the skills they need to self-assess, peer-assess, reflect, and give feedback. With a large group, there is no way that a teacher can be expected to give meaningful feedback to everyone or assess their progress. The best we can do is develop the skills above and help our students to become more autonomous.

Let’s bring it all back home.

It’s not that we disagree with any of the above challenges. They are all challenges. However, if we believe in the value of these discussions and so we urge you to persevere and make it possible for your learners. They can all do it…they might just need your support.